Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurological disorder that mainly affects movement, but over time it also impacts mood, sleep, thinking, and everyday independence. It happens when certain brain cells that produce dopamine—a chemical that helps control smooth, coordinated muscle movements—gradually stop working and die.

Parkinson’s is one of the most common movement disorders worldwide and in India, with prevalence increasing as populations age. Early recognition and a tailored management plan can help people live active, meaningful lives for many years after diagnosis.

What Is Parkinson’s Disease?

- PD is a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative disease characterised by motor (movement‑related) and non‑motor symptoms.

- The hallmark is loss of dopamine‑producing neurons in a region of the brain called the substantia nigra, leading to an imbalance of neurotransmitters that control movement.

Most cases are idiopathic (no clear single cause), though genetics and environmental factors both contribute.

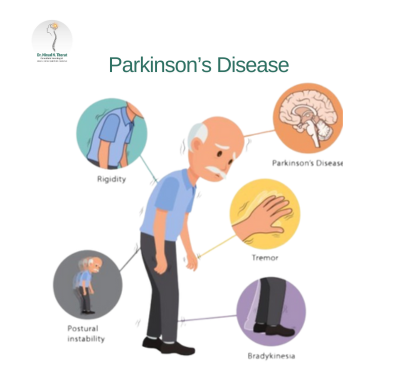

Classic Motor Symptoms

Doctors often summarise the core motor features as:

- Resting tremor

- A rhythmic shaking, usually starting in one hand (“pill‑rolling” movement), more noticeable at rest and improving with movement.

- Bradykinesia (slowness of movement)

- Difficulty starting movements, reduced facial expressions, softer speech, smaller handwriting (micrographia).

- Muscle rigidity

- Stiffness in arms, legs, or trunk; a “cogwheel” feel when limbs are moved.

- Postural instability

- Impaired balance and increased tendency to fall, usually in later stages.

- Impaired balance and increased tendency to fall, usually in later stages.

Not everyone has all four at the beginning; PD often starts asymmetrically on one side.

Important Non‑Motor Symptoms

Parkinson’s is more than a movement disorder; non‑motor symptoms can appear years before tremor or stiffness and strongly affect quality of life:

- Sleep disturbances – REM sleep behaviour disorder (acting out dreams), insomnia, restless legs.

- Loss of smell (hyposmia) – often an early sign.

- Constipation and urinary symptoms.

- Depression, anxiety, apathy.

- Cognitive changes – slowed thinking, later mild cognitive impairment or dementia.

- Autonomic problems – low blood pressure on standing (orthostatic hypotension), sweating abnormalities, sexual dysfunction.

Recognising these helps in earlier diagnosis and comprehensive care.

Stages of Parkinson’s Disease

Commonly, clinicians use scales like Hoehn and Yahr to describe progression:

- Stage 1: Symptoms on one side only, mild, little or no functional impairment.

- Stage 2: Symptoms on both sides, but balance is still intact; daily tasks may take slightly longer.

- Stage 3: Postural instability appears; falls may start; still independent but more limited.

- Stage 4: Severe disability; standing or walking possible only with assistance.

- Stage 5: Wheelchair‑bound or bedridden without help.

Progression speed varies considerably between individuals; many remain in early stages for years with appropriate treatment.

Causes and Risk Factors

Exact cause is unclear, but several contributors have been identified:

- Age: Biggest risk factor; PD rarely begins before 40, more common above 60.

- Genetics: Certain mutations (e.g., in LRRK2, PARK genes) increase risk; familial clustering is seen in a minority of patients.

- Environmental exposures: Pesticides, solvents, and some heavy metals have been associated with increased PD risk in epidemiological studies.

- Head injury: Repeated trauma may raise risk.

Most patients likely develop PD from a mix of genetic susceptibility and lifelong environmental influences.

How Is Parkinson’s Diagnosed?

There is no single blood test or scan that definitively diagnoses typical PD; it is largely a clinical diagnosis:

- Detailed history of symptoms (onset, progression, non‑motor complaints).

- Neurological examination looking for tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, gait changes, and postural reflexes.

- Response to dopaminergic medication (like levodopa) supports the diagnosis.

- MRI or other tests may be used to exclude mimicking conditions (stroke, normal‑pressure hydrocephalus, drug‑induced parkinsonism).

Special scans (e.g., DaTscan) can help in selected cases, but are not required for every patient.

Treatment: Medication and Beyond

Parkinson’s is currently not curable, but many treatments improve symptoms and function

1) Medications

Main drug categories:

- Levodopa (with carbidopa/benserazide)

- Gold‑standard symptomatic treatment; converts to dopamine in the brain and significantly improves slowness and rigidity.

- Over years, some patients develop “wearing‑off” (shorter action) and dyskinesias (involuntary movements), which can be managed by dose adjustments and add‑on drugs.

- Gold‑standard symptomatic treatment; converts to dopamine in the brain and significantly improves slowness and rigidity.

- Dopamine agonists (pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine)

- Mimic dopamine’s action in the brain; useful early on, especially in younger patients, often combined with levodopa later.

- Mimic dopamine’s action in the brain; useful early on, especially in younger patients, often combined with levodopa later.

- MAO‑B inhibitors and COMT inhibitors

- Prevent breakdown of dopamine, smoothing its effect and extending levodopa benefit.

- Prevent breakdown of dopamine, smoothing its effect and extending levodopa benefit.

- Anticholinergics and amantadine

- Used selectively for tremor or dyskinesias; side‑effects limit use in older people.

- Used selectively for tremor or dyskinesias; side‑effects limit use in older people.

Choice of regimen depends on age, lifestyle, job demands, symptom profile, and side‑effect tolerance.

2) Non‑Drug Therapies

- Physiotherapy and exercise – strength, balance, and flexibility training improve mobility, reduce falls, and may slow functional decline.

- Occupational therapy – strategies and tools to maintain independence with dressing, writing, cooking, and employment.

- Speech and swallowing therapy – helps with soft voice, slurred speech, and swallowing difficulties.

- Nutrition support – balanced diet, anti‑constipation measures, and timing protein intake in relation to levodopa doses for some patients.

3) Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) and Advanced Therapies

For selected patients with significant motor fluctuations or medication‑induced dyskinesias despite optimal drugs:

- DBS involves surgically implanting electrodes into specific brain areas (e.g., subthalamic nucleus) connected to a pacemaker‑like device that modulates abnormal signals.

- This can markedly reduce “off” time and dyskinesias, allowing lower drug doses.

Infusion therapies (e.g., levodopa intestinal gel, apomorphine pumps) are also used in advanced centres.

Living with Parkinson’s: Practical Management

Key pillars of long‑term management include:

- Regular follow‑up with a neurologist experienced in movement disorders.

- Staying active: Walking, stretching, yoga, tai chi, or dance can improve balance and mood.

- Home safety modifications: Grab bars, non‑slip mats, good lighting, reducing clutter to prevent falls.

- Mental health care: Screening and treatment for depression, anxiety, and cognitive changes.

- Support networks: Family education, local support groups, and counselling.

Caregivers also need information and respite support, as PD care can be emotionally and physically demanding.

Prognosis

Parkinson’s disease typically progresses slowly over many years:

- Many patients have good control of motor symptoms for 5–10 years or more with medications and therapy.

- Non‑motor symptoms and balance issues can become more prominent over time.

- Life expectancy can be near normal in well‑managed patients, though complications like falls, infections, and swallowing problems can impact health in advanced stages.

Early, holistic management improves function, independence, and quality of life.

FAQ

1) Is every tremor in the hands a sign of Parkinson’s disease?

No. Many tremors are not due to Parkinson’s. Essential tremor, anxiety‑related shaking, medication‑induced tremor, thyroid problems, and metabolic issues can all cause hand tremors. Parkinson’s tremor is more typical at rest, often starts on one side, and is accompanied by bradykinesia and rigidity. Any persistent or worsening tremor should be evaluated by a neurologist for proper diagnosis.

2) Can lifestyle changes or exercise slow the progression of Parkinson’s?

While no lifestyle change has definitively been proven to stop the disease, strong evidence shows that regular physical exercise, balance training, and cognitive engagement improve mobility, reduce falls, and support brain health. Many neurologists encourage tailored exercise programmes, social interaction, and mental stimulation as core components of PD care alongside medication.

3) When should someone with Parkinson’s consider deep brain stimulation (DBS)?

DBS is usually considered in people who: have had Parkinson’s for several years; respond well to levodopa but experience troublesome “on‑off” fluctuations or dyskinesias; and do not have severe dementia or uncontrolled psychiatric illness. It is not a first‑line treatment and does not cure PD, but for carefully selected patients it can significantly improve quality of life and smooth out motor symptoms. A detailed evaluation at a specialised centre is necessary to decide eligibility.